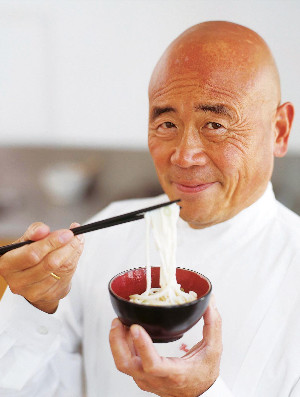

He’s written 18 best-seller books, sold almost 10 million woks across the planet and he’s been a celebrity chef since before celebrity chefs were even a thing – Ken Hom is a bona fide gastronomy legend. Honing his culinary chops in California and cutting his TV teeth in the UK, his dynamic career led him to charm audiences around the globe with a spate of successful shows. More recently, the beloved chef has catalogued his flavourful life in an autobiography: My Stir Fried Life.

Ken Hom, welcome back to Dubai – we understand you’ve been here before?

I’ve been many times! I’ve been invited to cook at Jumeirah Beach Hotel and did a pop-up restaurant at the Burj Al Arab a couple of times before Nathan Outlaw took over at Al Mahara.

We’re always curious to learn how a chef’s travels influence his or her work. How has your interpretation of Chinese cuisine evolved?

Just like the world is changing with globalisation, food is changing as well. For the first time we’ve been taken out of our comfort zone and been challenged by seeing how people do things in a new way. I’m learning all the time when I travel. I constantly see things I’ve never tasted or smelled and all that goes into the pot! That includes the Middle East and all of the spices you find here. You can learn from a book but there’s nothing like experience – experience is the most wonderful thing when it comes to food because food is so sensuous. It’s not something you can describe, it’s something you have to feel; put it in your mouth, smell it with your nose and see if it suits your taste. These are the things that make my work exciting.

Let’s backtrack to Chicago, where you grew up, before moving to California – where you went to college. How did you first begin to discover your passion for cooking?

I left Arizona before I turned one and growing up in Chicago I really stayed within Chinatown, so it was only California that influenced my cooking, where I was in the ‘70s. It was all about anti-corporate, anti-processed foods when everyone thought corporations were poisoning us, so we got into organic food. We were hippies! We were against the war and we were against processed food, and that was an awakening for me as well, because I learned about food sources and food that wasn’t sprayed with all kinds of shit.

California always seems to have had more of an awareness when it comes to GMOs and the organic movement.

Yes, and we began to doubt everything we were told so would investigate everything for ourselves to understand our environment. It was a hippy thing but it’s becoming the mainstream now – people understand that what we eat has a lot to do with our health. It also got me thinking about food waste. The fact that 40% of food in the UK ends up in the bin is outrageous, and it impacts on the environment, climate, sustainability – there are so many issues.

Why do you think there’s an increasing awareness of these issues now?

Awareness. The media. People writing about it. The pace of modern information sharing means that we instantly know about things, which is can be good and bad! But awareness is a good thing.

Chinese food in the West is totally different from everyday cuisine in China. Was that always the case?

Food is authentic in it’s own situation. People talk about authenticity but food is only authentic if it’s cooked properly. For example, take asparagus. It’s not Chinese, but why wouldn’t we use it if it’s available? That’s the strength of Chinese cookery, is that it’s able to adapt to wherever you are.

The Chinatown pockets in US cities can often be quite insular, so how have those communities fared in terms of forging their own culinary trends?

A lot of those communities were a bit of a bubble but that’s changed with immigration. Let me give you an example; in Chicago’s Chinatown, where I grew up, I only spoke Cantonese until I was six. English is my second language. And now if you go back to that same neighbourhood it’s completely different. We have people from other parts of China who’ve migrated there, so the food has changed. Before, it was the Cantonese food that I grew up with, but now the second, third and fourth generations have moved out, got an education and live in the suburbs. Chinatown is now packed with new immigrants so the core of it has changed – so has the food.

Can you give any examples?

Take Szechuan for example. My uncle only cooked one Szechuan dish, which a lot of people don’t eat because it’s spicy, and people from the south don’t like spicy food. Now, there two or three dedicated Szechuan restaurants in Chicago’s Chinatown, which is unheard of, and that’s happening everywhere. Chinatowns have changed in London and Liverpool, Paris and elsewhere. It’s a reflection of migration and immigration, which is a good thing and shows how we all benefit.

You have a vast library of books that you’ve written, so how does ‘My Stir-fried Life’ differ?

I’ve been cooking for almost 60 years now and this is a memoir of my very comic life! It’s filled with recipes and how those recipes reflect certain points in my life. It’s been a good life and I’ve done a lot, enjoyed a lot and learned a lot. I’m very lucky. I’m one of these people that sees life as a glass that’s half full, rather than half empty.

So what’s next? Are you still teaching and mentoring other chefs?

I’m now looking at a series on Chinatown, and I’m particularly fascinated by Chinatown in the UK. I’m going to be 70 soon, so there’s not a lot of time left! I’m involved in Oxford Brookes University, mentoring students. I also consult for various restaurants and maintain contact with many chefs I’ve worked with. It’s actually one of the best things I do; I’ve always regarded myself as a teacher first and that’s actually how I began my career.

And we have to ask about the famous wok. Is it true that you can find a Ken Hom Wok in one-in-seven UK households?

Yes! I was approached by at least 20 companies to do a wok and only one would allow me to have complete control. Eight million woks later, they’ve been sold in 72 countries. It’s constantly changing with new materials and technology. We didn’t start out as “non-stick” because there was too much heat. But I approve and test everything myself and I sign off on every modification. I know that if I wouldn’t buy it then why should someone else? I also said there would be no TV adverts, I’d rather put the money in my Chinese New Year tour, where I show people how to use the wok at different shops or venues. It was great for me because I learned so much about the UK! That actually got me better known than the TV show and I felt like a politician touring the country.

www.emirateslitfest.com/authors/ken-hom/