"You’ve got to try this bread ice cream,” a fellow food-writer friend tells me over brunch one Saturday afternoon. We’re having dim sum one floor below the place he’s speaking of, and pop up afterwards to sample the dessert. From the first bite to the last, it’s a revelation. To call the bread ice cream, so masterfully conceived at Mio, the Italian restaurant at Four Seasons Hotel Beijing, simply “ice cream” is unjust. A toasted, hollowed-out baguette crust cradles a parfait of bread ice cream, layered with raspberry purée and house-made granola, and topped with burnt white-chocolate powder, a drizzle of virgin olive oil and pearls of balsamic oil. Made from milk infused with rye bread crumbs and a touch of bergamot oil, it’s somehow exquisite yet hearty – our daily bread reimagined.

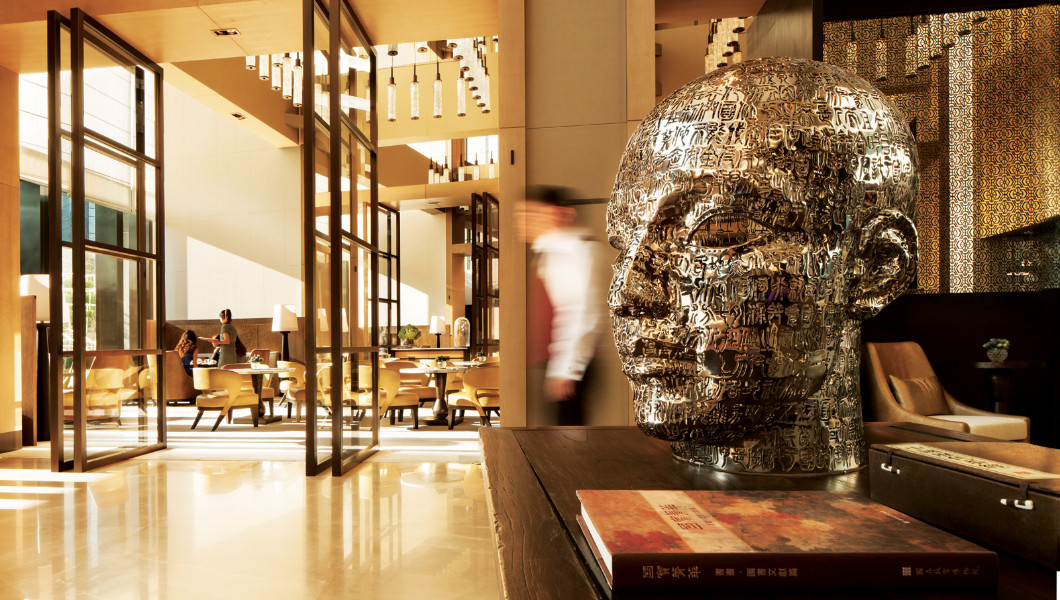

Indeed, a great deal has been reimagined since Aniello Turco took over the kitchen at Mio last year. In true Four Seasons opulence, the glittering crystal-drenched dining room, outfitted in deep reds, mahogany and dark marble recalls the Belle Époque, yet the food served is thoroughly modern. And arguably, it’s where the city’s most interesting cooking is taking place. Turco arrived in Beijing hot from a year and a half in the kitchen of Noma – the world’s best restaurant for several years and certainly the decade’s most influential. “Noma, Copenhagen and the environment there completely changes your life, your style, your visions, how you see the food, how you put it on the plate, and how the people react to that food,” says Turco. A fervent believer in all things fermented (possibly Noma’s signature technique), the 29-year-old chef bubbles over with boyish excitement – and fantastic intensity – when speaking about the cuisine.

Showcasing the aesthetic and attitude of what he learned in Copenhagen, Turco has developed his own identity and flair at Mio; sea bream in a charcoal sea-salt crust that resembles lumps of coal is opened tableside by the chef and served with earl grey tea-infused broccoli-stem purée, for example. Turco and the gastronomy offered at Mio is the first hint that the New Nordic revolution has reached China’s capital. More a movement than a set of dishes, ingredients or techniques, New Nordic cuisine has been the most significant force to grip the culinary world this past decade. Unlike most cuisines, its origins were deliberate and considered – crystallised in 2004 when a group of Scandinavian chefs signed the New Nordic Kitchen manifesto, a set of principals ardently committed to seasonality and regional ingredients. Established in 2003, Noma and its chef René Redzepi, now both household names, blazed the trail but perhaps more importantly, they cultivated an energetic community of chefs who have developed the New Nordic scene into what it is today.

The second hint of the Scandinavian trend sweeping across the city blew into Beijing with the autumn breezes in November, where in the winding alleyways of Beijing’s historic hutong neighbourhoods, Copenhagen’s luxury-silver brand Georg Jensen opened its first-ever restaurant concept – and first showroom in China. The Georg (45 Dongbuyaqiao Hutong; +86 10 8408 5300) is an entirely new style of dining experience in the city. Set in a gorgeously renovated courtyard building, the impossibly chic, minimalist space is all clean lines, smooth concrete and spectacular natural lighting – very Scandinavian – but the tasting menu’s ¥450 (US$68) price tag belies the white-linen tablecloths. Upscale yet casual, refined yet relaxed, The Georg is paving a Beijing trend for restaurants that are laid-back and – very outspokenly – not fine dining, but offer, in their words, “focused” food. An exceptionally delicate seared medallion of foie gras, glistening on a plate with fried rounds of Jerusalem artichoke and powerful fermented black-bean sauce is just one dish you might encounter.

While Noma might be the godfather, it’s the next generation of chefs who emerged to launch other Copenhagen restaurants that The Georg restaurant manager Stefano Censi and chef Talib Hudda – who worked together at the Michelin-starred Marchal – name as their inspiration. “Noma was the spark plug that gave these chefs creativity, a voice and a platform,” says Censi. “It’s that secondary thing that spawned – that is what we came from.” Ten years on, New Nordic has evolved into a lifestyle, an aesthetic, a style of service, an attitude and most of all, a philosophy – and diners in Beijing are lapping it up. While many affluent Chinese may still believe food should be draped in lush shavings of truffle or weighed down with a small mountain of glistening caviar, attitudes are changing – and fast. As more Chinese travel internationally, they are seeking to challenge their palates at home. “What are affluent diners seeking?” asks Yang Xiaoxu (Emily Young), a restaurant critic for popular Chinese-lifestyle website www.dailyvitamin.cn. “I think an element of surprise and health.”

New Nordic ticks both boxes, especially in a country where health has evolved into a serious concern. News of tainted foods like melamine-spiked milk and plastic rice or the use of recycled gutter oil and, most recently, opium powder as seasoning, has dominated headlines – and then there’s the pollution. Red alerts that invoke a citywide shutdown were implemented by the government for the first time last year; it’s a reality check for anyone who wasn’t admitting the severity of the situation. Today, Beijing residents are growing increasingly aware of their health and it’s all impacting consumer demands. Traditionally, the Chinese have always connected food with health benefits, and now they are asking how it can mitigate the pollution, says Jens Wycisk, the food and beverage director at the Four Seasons. “We’ve seen the trend for a while now but it’s going more and more towards food quality, food safety and all that is healthy – quinoa, sorghum seed, avocado.”

Throughout the city, chic cafés pushing fresh smoothies, salads and vegan concepts have become en vogue, with more juice-cleanse companies than you’d imagine an emerging world city might need, 20 million inhabitants or not. A fixation on craftsmanship has washed over the city, too. “It’s going more artisanal,” explains Wycisk. “We have expats and locals who are taking the artisan approach, like with coffee roasting.” He refers to third-wave coffee-haunt Soloist Coffee Co. (39 Yangmeizhu Xiejie; +86 5711 1717) as an example. Elsewhere, other Beijing chefs are focusing their attention on sourcing as sustainably and locally as possible. There’s Max Levy at the excellent modern-Japanese restaurant Okra (1949 The Hidden City, Courtyard 4, Gongti Bei Lu; +86 10 6593 5087) who sources his produce from a small nearby farm; and the capital’s newest upmarket international hotel Rosewood Beijing (Jing Guang Centre, Hujialou; +86 10 6597 8888), which sources a portion of its ingredients from sustainable local partners.

“New Nordic is really a philosophy of foraging, of wild products, and here you cannot find any wild stuff,” says Turco. “The philosophy of Nordic is also local – and what is local here? Nothing. Wild local? Nothing.” Chefs hailing from the New Nordic scene have often remained in familiar Copenhagen or settled in lush regions like Washington state or New York with its fertile Hudson Valley and Brooklyn’s Prospect Park where you can sign up for foraging lessons on weekend afternoons. In Beijing, they wage a battle against a naturally desolate environment where sandstorms whip through the city in the spring and, more uniquely, toxic pollution taints everything – the soil, the air and the water. Foraging seems an impossible proposition in this dystopian landscape. Against all the odds, they are taking a modern cuisine that promotes locality and trying to adapt it to an even more inhospitable part of the world, a region and climate known for its sparseness, its bleakness – and now its pollution.

It’s a challenge not lost on Beijing’s New Nordic tastemakers. “Nordic inspiration is what the landscape gives to you, and [what] you can make on a plate, but here it’s a different thing,” Hudda says. Censi nods in agreement. “The landscape’s not really giving you anything.” But both remain positive, Hudda referring to legendary New Nordic chef Magnus Nilsson at Fäviken [in Sweden], who has spoken about his greatest inspirations materialising when under pressure. It’s a high bar these New Nordic chefs have set but the promise of evolution – and the journey to come – makes them ones to watch in Beijing.