You’re here for the Emirates Festival of Literature, having just published your book, Journeys in the wild. Have you been here before?

I’ve been through the airport many times and I filmed the Arabian Oryx for a Netflix show called Our Planet which was shot in Oman and at Qasr Al Sarab in Abu Dhabi − that was really special. The desert was absolutely stunning and the traditional architecture was beautiful. I’m not a huge fan of cities, but the surrounding countryside was amazing,

and it was wonderful to see the oryx doing so well in the wild.

Let’s go back to the beginning, with your trip to Dudley Zoo in 1972 and a photo you took of an orca whale. Was this where it all started?

Yes, I suppose it was. I do vaguely remember the trip itself,

for which I took my camera, but it was the moment of picking the photographs up from Boots afterwards, as you had to do in the those days, that was the most astonishing thing. I’ve got

a very visual memory and seeing that photograph of the whale exactly as my memory saw that event two weeks before, and then being able to share it, well that was the most important thing. I still have the photograph. I could bring it to Dubai and you’d see the exact moment, almost 50 years ago when

I pushed that camera button... It was kind of a revelation to me. While it’s actually very simple to take a picture, and we all take pleasure in doing it now, hundreds of times a day,

the defining moment for me was the two-week anticipation and then getting that photo back. Definitely more rewarding than the instant gratification you get from taking an iPhone picture.

Was it always photography you were interested in, or other arts too?

At school I was keen on art, as I had a really good art teacher who encouraged us to try different things, and while I had the same tools, the same brushes, the same paints in my hand that Van Gogh and Picasso had, I could not get anything onto the paper that remotely resembled what was in front of me!

No matter how I tried, I just couldn’t put what was in my mind onto the canvas, it was so frustrating. But with photography it was so much simpler. So discovering photography as a hobby fulfilled that passion I had to be an artist of sorts, as well as fulfilling that yearning to be able to share a moment.

What then steered you in the direction of wildlife photography?

At the time, you don’t realise these things, but writing this book, Journeys in the Wild, I look back and see what it was that instilled the passion in me. A lot of it comes down to my mother’s mother. She always had nice houses in the countryside, and my sister and I would be farmed out there for holidays, and she knew all the common names for all the flowers, the trees, the Latin names... We used to go for long walks in the countryside, press flowers and leaves. She used to take me to a place called Selborne in Hampshire − which was the family home of Sir Gilbert White, an 18th-century British naturalist − where there was a path called the Zig Zag. I’d walk up it with my granny who was

a font of knowledge, and a real passion for nature, and I think when you’re with someone so passionate and knowledgeable about the nature around you, it rubs off on you. So, on the natural history side,

my granny was certainly a huge influence.

Can you recall your first ‘professional’ assignment?

I would probably say it was sweeping floors, and making sandwiches and cups of tea at Oxford Scientific Films, which is a very small film company just outside of Oxford. I got a holiday job there the day I left school, but this way I got to see all the people and all the facets of the industry, from sorting slides in the slide library, to the commercial department, to filming on the natural history side... It was a great way of getting a full spectrum. Nowadays, people leave university and expect to get a job, but all you really have is knowledge and a piece of a paper. If you’re going into the film industry, you really need to start at the bottom. So joking aside, that really was my first professional assignment - professional floor sweeper.

What was your time like working there,

as your first foray into the world of

natural history and filming?

Oh, it was wonderful. One of my first memories of when

I recall first really marvelling at the natural world was with this small set up we had in a studio of some hazel leaves and branches,

with a cameraman who was filming a tiny little leaf-rolling weevil. Through the day the weevil went through this intricate origami trick of tucking, folding and rolling this leaf into

a little roll, before turning around, sticking its bum into it, laying an egg and then moving off and doing it all over again.

We filmed it eight or nine times and it was just amazing. Nobody had taught the weevil to do this, but it just knew. It made me think, I’d never seen one of these before but I’d probably walked past hundreds of them in the woods and never noticed them,

so what else haven’t I noticed? So the next time you’re out, start looking for everything else, and once you have that inquisitive mind and that passion for it, you’ll never lose it. 50 years down the line and I’m still being shown things by scientists and discovering new behaviours. The natural world is almost infinite in terms of what we can discover.

How then does one help inspire and incite passion in the next generation?

I think every child has a fascination for everything. If you put a worm in the hand of a three year old, he won’t squirm away from it, he’ll just be intrigued and interested and look at it.

It’s the same with anything. The squirming only comes if the child is taught to be repulsed by or be wary of something.

So I think all kids start out with that wide-eyed wonder of the natural world, and I think it’s about finding a way of continuing that without putting people off.

Do you feel a sense of responsibility with the work that you do to promote our planet?

Well, I get lots of lovely trips around the world to see all kinds of marvellous things, but the end product is a global product, which is important. Take the most recent project I’ve worked on, Our Planet for Netflix, which went live last April. It reached a global audience of 138 million people in the first month alone and they estimate that in its 10-year run on Netflix, it will be seen two billion times, which is almost a third of the global population. And if that means that people ‘Ooh’ and Ahh’

at all the amazing animals and scenery, hopefully it will instil a passion in them to want to know more, to visit these places and help protect them. That said, you can’t force people to be passionate about something, all you can do is open the door, show them the view and hope they are taken in by it. Eventually one of the doors that you open will be the thing that your child is passionate about. So the more doors you can open, the better really, and television is like opening a door to the world.

Do you feel your work has a positive effect on the environment and people’s attitudes towards it?

Yes, I think so. I do feel particularly guilty in my industry because we fly around the globe with hundreds of kilos of kit, so my carbon footprint is massive, but I’m trying to do things to change that. What we can all do to limit our impact on this planet is just not to waste. I think Blue Planet 2 was a real catalyst for change. People’s attitudes to plastic bags and straws has really changed, very recently and in a very short space of time. People had been campaigning for years and years to stop plastic, but I really think the final catalyst was those images from Blue Planet 2.

When have you seen nature at its best?

It depends on where you ask me and when. Today, I saw

a little robin sitting outside singing its heart out. And to see that in my back yard was pretty magical. Equally, seeing a herd of wildebeest moving across the plains of the Masai Mara is also very magical. Everywhere you go nature is beautiful and amazing. That’s why I think nature is so universally loved -

we all find something different in it.

When have you seen nature at its best?

It depends on where you ask me and when. Today, I saw

a little robin sitting outside singing its heart out. And to see that in my back yard was pretty magical. Equally, seeing a herd of wildebeest moving across the plains of the Masai Mara is also very magical. Everywhere you go nature is beautiful and amazing. That’s why I think nature is so universally loved -

we all find something different in it.

Now, you’ve worked with Sir David Attenborough for over 30 years. I’m sure you get asked this a lot, but what is he like?

The first thing about David is that he is as nice as you can imagine. He’s just a decent bloke. He’s a friend, a mentor,

an expert - he’s super, super knowledgeable on so many things, so any time you can spend with him is just an absolute pleasure. He’s also the best travel companion. If you’re driving through the Atlas Mountains and you see an interesting rock, David will know what the rock is, how old it is, when it was formed...

He’s like a walking encyclopedia. But not in a know-it-all way,

but more in fuelling your interest with his answers. He’s also great fun and very down to earth. He likes a glass of wine,

he’s very sociable and enjoys being part of the team. He never makes any demands at all. In fact, it was only when he was in his seventies, shooting The Private Life of Plants, that he started flying Business Class, and that wasn’t his choice - the production team wanted him to, so that he could relax and be fresh for filming.

Tell us some of the wonderful memories you have of your time working with him

I remember us filming chimpanzees for Life With Mammals in the swampy island area of Conkouati in Democratic Republic of the Congo, working with a charity that introduce orphaned chimpanzees back into the wild. The chimps have these special techniques to eat and survive, such as cracking palm nuts, which they have to learn, or they have learned that at low tide they can rise up on two legs, hold their hands in the air (they don’t like getting them wet) and wade between islands to make more use of the land space. So David is there doing his piece to camera, about chest deep in water wearing waders, talking about our distant ancestry, as chimps wade around behind him. To have that whole package of David’s words and to see what he’s talking about happening right behind him, was just so completely magical that the hairs on my neck stood up. It was an extraordinary moment.

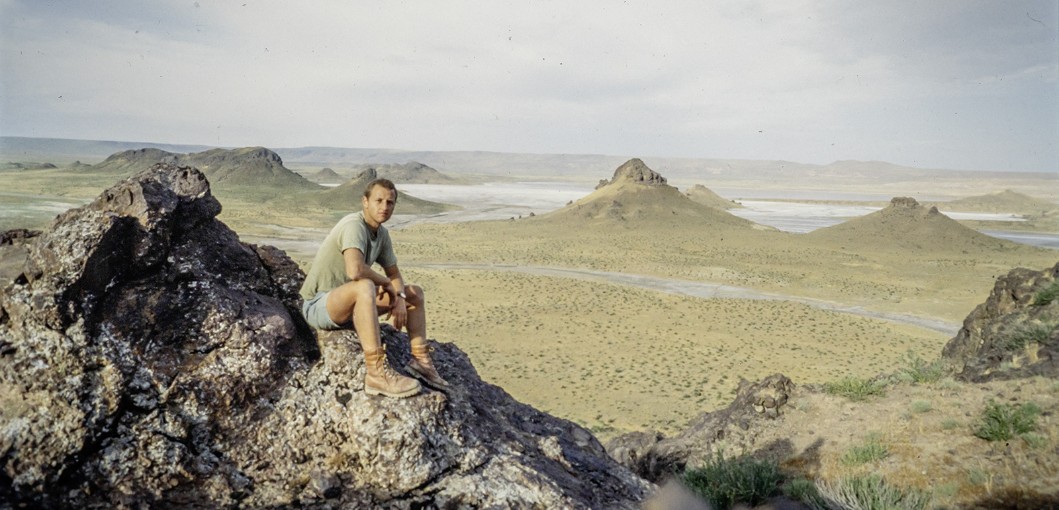

What attributes do you need for your job?

Some people say patience, but I don’t think so. To sit in a hide in paradise somewhere in Africa, waiting for a bird or a gorilla to return to its nest, sitting there for 17 days before you see anything... That’s peaceful, because you’re surrounded by nature, there’s no pressure to get anything because you can only film what happens or what you adapt to. So not necessarily patience. But you do need a lot of passion for wildlife if you want to be a wildlife photographer. You also need to be fairly technical as a cameraman and have a good photographic eye, and an idea of storytelling for video sequences. And you also need to be adaptable, so that you come back with something, some kind of story, even if it wasn’t what you initially went out to film. Being physically fit also helps, as there’s a lot of kit to lug around, but that said a lot of times when you’re shooting in the Masai Mara or Serengeti it’s all vehicle-based, so you’re actually just sat in the vehicle for 12 hours a day, for seven days a week, for six weeks stuffing your face. And it’s not like you can go for a run in the evenings, because something will eat you! You’ve got to run 70mph to outrun some animals out there, and not even Usain Bolt can do that! But a lot of people save up all year round to spend a week in the Masai Mara or trekking somewhere, and I’m being paid to do it.

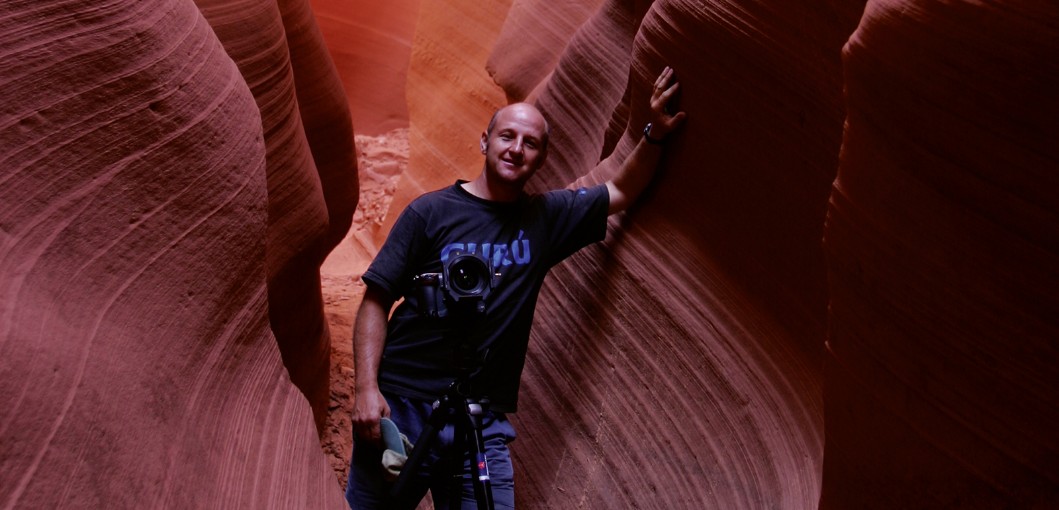

What do you never leave home without?

Binoculars, speakers, Marmite, Colman’s Mustard, ear plugs in case you’re in a tent next to someone who snores, a silk sleeping bag liner, my trusty Ronford tripod, my favourite walking boots, and a hat.

Where would you most like to live?

If I couldn’t live in Bristol in the UK, New Zealand would be my first choice. It’s a beautiful country, low population, a nice range of things to do, lots of wild space with interesting flora and fauna, with an almost tropical climate in the north to fjord lands in the south.

Lastly, what’s next for you?

I’ve just been in Antarctica for six weeks where I filmed the helicopter aerials for Frozen Planet 2, which will come out at the end of 2021. Then I’m working on a series called Mission OceanX, with James Cameron, on a groundbreaking ocean exploration mission that harks back to the days of filmmaker Jacques Cousteau. And then I’ve been working on a feature

film with David Attenborough about his 93 years on this planet, how we’ve messed it up and how we can fix it. It’s called

David Attenborough: A Life On Our Planet, and it’s being

released on April 16.

Gavin Thurston will be speaking at the Emirates Airline

Festival of Literature on February 6 and 8, and his new book, ‘Journeys in the Wild’, is out now

www.emirateslitfest.com