"Welcome to paradise!” shouts this Bob Marley-esque man wearing a faded vest and shorts, looking to lure tourists to his bicycle rental. Somewhere else this may sound trite, but here on La Digue, the third most populous island of the Seychelles, I look around and nod in silent agreement. With long, sunny days, countless strands of uninhabited, blindingly white sand beaches, bendy palms and clear waters in every shade of Pantone blue, the cluster of 115 islands that make up the Seychelles, could well be the visual definition of the word.

Armed with a map and a change of clothes, my husband, nine-year-old daughter and I surrender to the persuasive charms of the bicycle vendor and head off to explore the small island on wheels. Once I find my balance, I begin to relax. I fall behind but there’s no hurry to get anywhere. Pedalling is meditative and the slowness that ensues is just the pace suited to island exploration. We make our way to Anse Source d’Argent (Anse, French for beach). One of the most photographed beaches in the world, it shot to fame when featured in Tom Hanks’ 2000 movie, Cast Away. We ride deep into the L’Union Estate, through coconut and vanilla plantations, past a large tortoise pen before leaving our cycles to walk a pathway strewn with gigantic granite boulders going up to the beach. The weathered brown, black and grey boulders are scalding hot as they bake under the harsh sun. Their appearance is bewildering on the fine, white sand, but their presence is what distinguishes Seychelles’ beaches from any other.

The cool waters of the knee-deep sea are a welcome respite from the heat. I keep my eyes trained on the ocean floor and surrounding coral heads so as not to miss a thing. For long stretches of time there’s nothing but the sun shimmering on the sand, and then, suddenly, a tiny, colourful fish darts by leaving magic in its wake. I wade a little deeper, and smile like a child as I’m surrounded by schools of scissortail sergeant and countless other small fish. It’s a privilege to be let into their lives like this and a moment to revel in.

Back on the strip of beach that oscillates between busy and quiet as day-trippers ebb and flow, we find a spot under the broad leaves of low lying takamaka trees and stretch out.

Fiona, a native of the island, runs the sole refreshment shack and sells an array of tropical fruits fresh from her garden. Her stall is a riot of colour, awash with juicy, tart starfruit, speckled green mangoes, crinkled passionfruit, poky pineapples, plump bananas and enormous green coconuts. As we stand chatting, she asks me to take a few sips from my coconut while she pulls out a bottle of Takamaka rum. A capful goes into my coconut, decorated with a bright red hibiscus flower, and there I am with a perfect cocktail, island-style.

As a family, we consciously decide to stay away from technology this trip. Except for occasionally checking in with our loved ones, we opt for a digital detox in the hope it will let us slow down and create deeper bonds with one another.

Our city-bred daughter, initially hesitant of the untamed outdoors, slowly embraces it. Scurrying crabs startle but don’t scare her. Missing our dog back home, she befriends a stray pup on the beach, and I love watching them run and splash around in the shallow waters without a care in the world. And with no distractions of my own, I find myself crackling present to everything around. Even my book lies ignored, as I bask in the sublime pleasure of doing nothing. Closer to evening we leave in time to catch the last ferry back to Praslin.

Our days in the Seychelles begin to follow a rhythm underlined by slowness. It gives us ample time to chat with fellow visitors and locals. A former French and British colony, the Seychellois are fluent in both French and English. These interactions, although fleeting, add a richer experience to the place. They also lead us to hidden gems, like La Goulue on Anse Volbert in Praslin. The no-frills restaurant serves scrumptious Creole food. Ravenous as holidays can make one feel, we wolf down plates of fish and vegetable curry served with hot rice and sides of chutney – mashed and smoked aubergines, and one made from pumpkin. The fragrant curry is spiced with a special Creole curry powder and cinnamon leaves found in abundance across the island. The spice and heat are perfectly balanced by ice cold Seybrew beer, another local favourite.

At Les Rochers, considered to be the best restaurant in Praslin, we get a taste of a more refined curry for dinner. We grab a corner table under its thatched-roof, and while we can’t see much at night, the ocean makes its presence heard with the sound of crashing waves. The restaurant, known for its fresh seafood and grills, gets booked out fast. After dinner we browse through the small onsite souvenir store that sells handmade products from across the Seychelles, including the prized coco de mer seeds.

The Vallée de Mai nature reserve, one of the last few untouched corners of the archipelago, is the best place to explore a thriving habitat of the coco de mer trees. The 19.5 hectares UNESCO Heritage Site is Praslin’s biggest tourist draw besides Anse Lazio and Anse Georgette. British army officer Charles Gordon, who visited the area in 1881, was certain he had chanced upon the probable Garden of Eden. We follow our affable guide Ronnie into a pristine habitat that feels prehistoric in every way except for the signboards and narrow path snaking through. Home to six kinds of palms, some towering over 100 feet tall, Ronnie teaches us how to distinguish the different varieties and tells us stories about the baffling coco de mer trees. The dioecious tree takes between 25 to 50 years to reach maturity and there are many legends about how they are pollinated. The most fascinating amongst these is the story of male trees marching up to female trees to ‘mate’ on stormy nights.

Vallée de Mai is also the best place to spot the rare black parrot endemic to the Seychelles, and found only on Praslin and neighbouring Curieuse island. Although a sharp, whistling call cuts through Ronnie’s narration, the bird remains well-camouflaged and out of sight.

The love nut, as the coco de mer is called for its curious heart shape, follows us everywhere, from the stamps on our passports and signages around the islands, to the welcome chocolates in our room at the Constance Ephelia in Mahé . The largest island of the archipelago, Mahé is home to the majority of Seychelles’ population and the small capital city of Victoria. A short, exhilarating plane ride in a tiny aircraft over aquamarine blue waters takes us from Praslin to Mahé, the last stop on our two-week holiday.

Situated in the shadow of the Morne Seychelles National Park, with two of the island’s best beaches and overlooking the Port Launay Marine National Park, Constance Ephelia’s fantastic location on the island’s western edge is hard to beat. It’s little surprise that the sprawling resort – with over 300 rooms, suites and villas – runs full almost year round.

After the peaceful vibes of Praslin, Ephelia’s upbeat atmosphere makes for an interesting change of pace. Our daughter is happy to have more company, as well as the choice of myriad children’s activities to pick from. The dedicated kids club (for four to 11 year olds) keeps her occupied with arts, crafts, games and nature walks, and a team of well-trained staff and on-hire babysitters allows us to relax and dive into some downtime too.

My husband and I settle into an easy routine: mornings spent relaxing by one of the hotel’s many frangipani-fringed pools, before gravitating to the north beach late afternoon, where we settle into beach chairs under the canopies of Indian almond trees. We stay until the sun’s last rays give way to an inky sky perforated with stars.

Bitten by the snorkelling bug in La Digue, I’m straight back in the ocean to find gigantic coral heads bursting with fish and other sea creatures close to the beach. We also go on guided treks through the hotel’s expansive property. On the moderate Ros Lepa trail we trek through dense tree cover with scuttling skinks for company and onto a hidden beach. The real treat is sweeping views of the roaring sea and nearby islands from a precipice overlooking what appears to be giant steps cut into the rock face. Our daughter, who is fascinated with mangroves having learnt about them in school, enjoys Sustainability Manager Markus Ultsch-Unrath’s walk, which takes us right through the hotel’s vast mangrove patch. She is wide-eyed as Markus picks up palm spiders, skinks and iridescent green geckos, and even musters up the courage to let one crawl up her arm.

Although Ephelia is a microcosm of the Seychelles giving guests little reason to leave the property, we hire a car and explore Mahé on our own. We eschew the island’s public beaches and head to the Takamaka distillery, where smooth rum with heady notes of coconut and local spices awaits. The back story tells us of two men and their dreams of creating a spirit that reflects the ethos of the magical islands they call home.

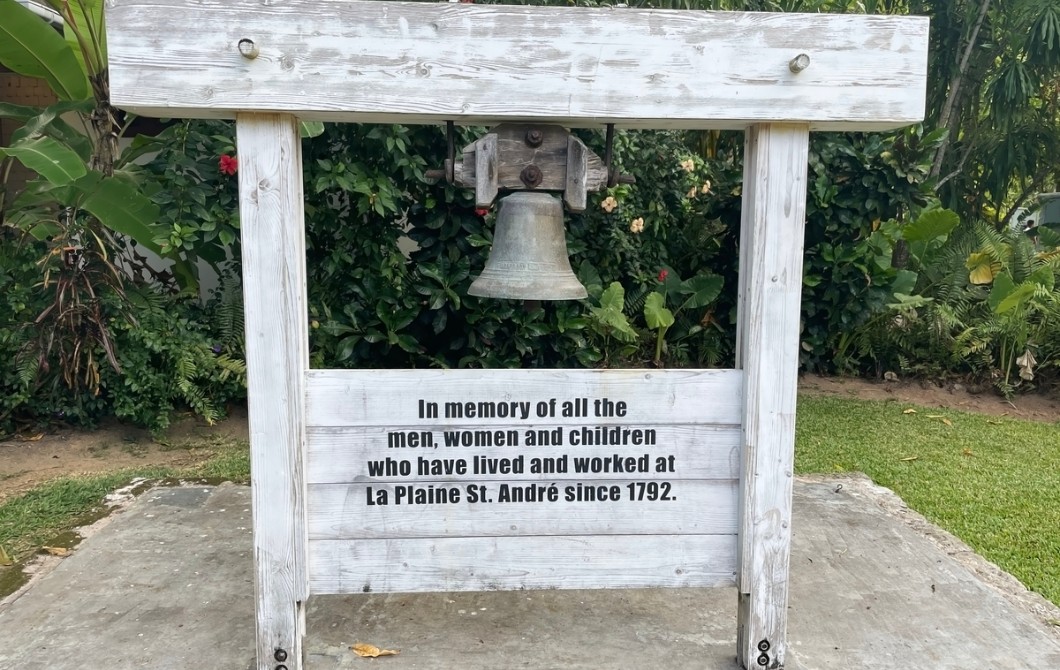

Located just off the beach, La Plaine St. André, the heritage building housing the distillery, museum and shop, dates back to the 1800s. The now beautifully restored white bungalow with thatched roof and solid wood louvered windows belonged to the Jorre de St. Jorre family. We spend time exploring the medicinal garden and the resident Aldabra giant tortoises, Taka and Maka, before joining a motley bunch under the shade of bilimbi trees for a guided tour. “Richard and Bernard d’Offay grew up in a family that only drank rum and so they wanted to make their own,” relays our guide Radicea, who explains how inextricably intertwined the rum and the island is.

A tasting caps the tour and we sample six rums produced in the distillery. The Dark Spiced rum, a best-seller with top notes of cinnamon, vanilla and papaya is an instant favourite. Radicea says another crowd-pleaser, particularly with the ladies is Koko, a white rum infused with coconut extract.

Like everywhere else in the world, Covid-19 has deeply affected the Seychellois islands and people, decimating many livelihoods. But they are still standing strong and still smiling. And it is the kindness and spirit of the people we meet that has really inspired us to relax into our two-week sojourn, truly let our hair down, and re-engage with people from all walks of life, especially the Seychellois. It was an important trip for our daughter too, to see the world once again through inquisitive and curious eyes, and to fall back in love with the joys of travel, on our own terms. As a family, the Seychelles is a place that invites detachment, where phones and other intrusive digital paraphernalia are given a back seat, and replaced with reality. The here and now. The people and experiences right in front of you. It’s rewarding and gives a whole new meaning to ‘slowing down’. In fact, I’m so relaxed that I’m writing this almost horizontal. Almost, but not quite… I’ll save that for my next trip.