A hand shoots up in the air. It’s our signal to be still and silent. Moli, our expert wildlife guide in Ruaha National Park, taps his little bag of ash, monitoring the direction it carries on the wind. On the dry riverbed, 20 metres ahead of us, a big-tusked adult male is just starting to figure out he has company. “It’s important they don’t see, hear or smell you,” Moli explains. “If one molecule of human scent touches that trunk, they know exactly where you are, and they don’t like it.”

We watch, motionless, talking in whispers for 15 minutes, the giant near enough that we can hear branches being chewed up by its powerful teeth.

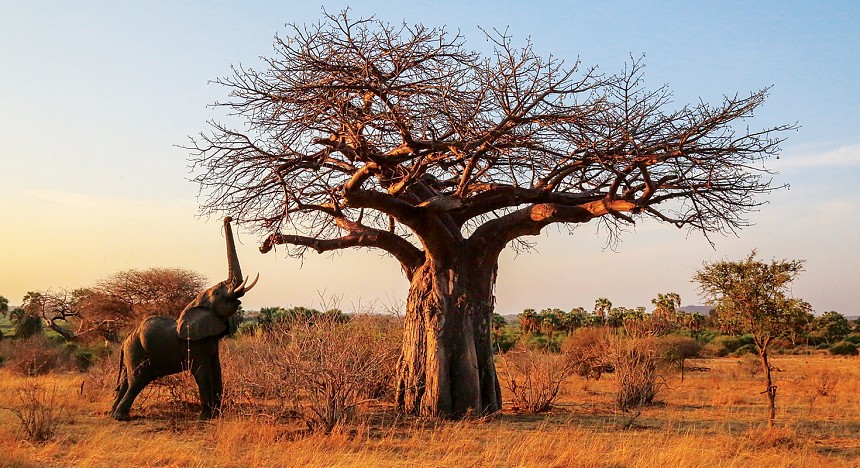

We find a herd of elephants wandering the dry Mwagusi riverbed, babies ambling between their mothers’ legs for protection

This close-up, ground level encounter is just one of many memorable experiences in Ruaha National Park. Tanzania’s largest national park, 20,226 sqm, Ruaha is still largely unheard of around the world; almost 40 per cent larger than the Serengeti, it receives less than 10 per cent of the visitor numbers. There are only 10 camps and lodges within the park’s borders, with tourism in just 10 per cent of the national park, leaving 90 per cent still largely untouched.

Here, you find world class wildlife, without the crowds you often get in the Serengeti, Ngorongoro or the Maasai Mara, the vast, remote wilderness home to one of the continent’s largest lion populations (around 10 per cent of the world’s remaining lion population), Tanzania’s largest elephant populations, one of the largest remaining cheetah populations, as well as leopard, hyena, giraffe and 574 species of colourful birds, including the endemic Ruaha hornbill. The landscapes are just as diverse as the inhabitants, from baobab forests to rocky outcrops, open savannah to the winding blue-green of the Great Ruaha River itself, which the park’s named after.

I fly into Ruaha’s Jongomero airstrip from Dar Es Salaam, my trip arranged with Audley (www.audleytravel.com/tanzania, +44 1993 838545), and make my first stop at Jongomero Camp, a permanent tented camp on the banks of the Jongomero river in the south of the park. The camp has eight spacious safari tents, each with a makuti-thatched roof. Inside, there are characterful antique-style trunks, lamps and hefty wooden furniture, including a bedside table, crafted from wood reclaimed from old dhows, traditional boats that have sailed Tanzanian’s coast for centuries. In one corner, there’s a writing deck, a comfy curvy brown leather armchair in another.

The greatest luxury here, though, is the feeling of being in the wilderness. The closest camp is 50 kilometres away, the nearest town, a 6-hour drive. Sitting on the wooden deck, the only sounds are insects, birds and occasionally elephants trumpeting. During lunch, a group of elephants appear across from the open-air restaurant, stripping branches of their leaves.

On an evening game drive, we see impala, warthogs and baboons inside a forest clearing. Black-backed jackals watch tawny eagles in the trees, hoping they drop morsels of food.

Next morning, we find crocodiles basking on the muddy banks of the Ruaha river. Hippos snort and sniff as they wallow in the cool water. A procession of elephants cross the river, massive adults pausing to give us a warning glare. “Ruaha comes from the old He-He word ‘Ruvaha’, meaning ‘the old river that never gets dry’,” guide Theo Myinga tells me. “Without the river, there’s no national park. The hippos, crocodiles, lions, buffalo… Everything here needs water.”

We leave behind the thick thorn tree forests around Jongomero and drive north to the central Msembe airstrip, where I meet Tony Zephania, head guide at Kwihala Camp, to explore the heart of the park, from baobab forests to the grassy plains of ‘Little Serengeti’.

We find a herd of elephants wandering the dry Mwagusi riverbed, babies ambling between their mothers’ legs for protection. Further upriver, Tony turns the vehicle toward a bottle-laden bar out in the riverbed for ‘sundowners’, before making our way back to camp.

Kwihala’s an incredibly friendly camp, somehow managing to run like clockwork (morning wake-up calls and heated water for bucket showers arrive on the dot) while maintaining a relaxed atmosphere. The only type of ‘inconvenience’ you might experience is having to divert your walk across to the main tent if elephants happen to be passing through the un-fenced camp, which only adds to the wilderness feel.

Spacious canvas tents look out towards the Mwagusi river and hills beyond. Dinner’s often served outside, under the stars, close to a blazing fire. Spicy fish curries and inventive salads would be delicious in any restaurant, but in this setting, it’s on another level.

More importantly, the wildlife guides here are knowledgeable, passionate and determined to get guests the kind of sightings or photos they want (nature allowing). We watch baboons feeding on baobab flowers, tree agamas of nature-defying colours sunning themselves on rocks and bandied mongoose foraging through the undergrowth.

A leopard moves from its hiding place, behind a baobab, to follow a herd of kudu. Later, we watch a 13-strong pride of lions feeding on a giraffe carcass.

Next day, we watch a cheetah sipping water from a pool in the Mwagusi riverbed, anxiously glancing over her shoulders. An adult male leopard appears on the bank, sets his sights on the cheetah, lowering his head to attack. Cheetahs are the weakest and most vulnerable of the big cats; leopards can sometimes chase or attack and kill them, a pre-emptive strike over territorial rights and feeding grounds.

The slim female cheetah looked terrified as the powerful, male picked up its pace and bore down on her. It would not be an even fight. But the cheetah had an advantage over the leopard’s bulk: speed. As the bigger cat neared, the cheetah turned and sprinted away, disappearing into the long grass to live another day.

We find the same leopard again later by following the sound of a disturbance: baboons shrieking angrily up at the branches of a sausage tree, where the big cats hiding. Despite their alarm calls, an oblivious impala grazes around the base of the tree. A chance too good to miss, the leopard bounds down the trunk and leaps at the careless impala. The impala struggled, but it was no match. “My word, what a bold move,” said Tony, shocked. “I’ve never seen a leopard hunt from a tree before. It’s so rare.”

The birdlife in Ruaha is remarkable, too, with Ruaha hornbills and lilac-breasted rollers flitting from tree to tree, African fish eagles soaring above, and Eastern Chanting Goshawks surveying the landscape.

I move across the park to Jabali Ridge, run by Asilia, the same company behind Kwihala, but with a different feel; more luxury retreat than safari camp. Opened in 2016, it’s the newest, grandest lodge in Ruaha, positioned high on a rocky outcrop (Jabali means ‘big rocks’) between the Mwagusi and Ruaha rivers. The central building has a stylish infinity pool and an excellent library, with a lounge, restaurant and open decking areas all with views out across the park.

Each of the seven bungalows combines sculpted cement with dark wood, the large doorways, slatted windows and a wooden deck (complete with hammock) designed to give the feeling of openness and being out in nature. The interior, however, feels like a smart, boutique hotel, with wooden floors, industrial grey bed linens and a massive shower room with a constant supply of hot water.

On the same property, but a separate entity, Jabali Private House sleeps a family of six. The décor’s the same mix of chic earthiness as in the bungalows, but families here get their own private chef, private butler, private game vehicle and guide, a kitchen and lounge area with everything from chess sets to beanbags, and their own swimming pool. It would make a memorable base for a wild family adventure.

On an afternoon game drive, I see the now-infamous leopard one last time, resting on a termite mound. At night, under a full moon, we go out again, wildlife guide Moinga Timan scanning with a spotlight for reflections of eyes, locating five spotted genets (like mini leopards), a rarely seen civet and a spotted hyena.

But I also get to explore on foot, setting out next morning with Moinga and an armed ranger. We spot an infant hyena and inspect a massive elephant skull, then climb uphill to a viewpoint; four Maasai giraffe stare curiously back at us from a baobab forest.

My final stop is Kichaka, a tiny camp of just three tents, run by Noelle Herzog and Andrew ‘Moli’ Molinari, out in the remote east of the park. The tents are beautifully done, with a writing table and stool, a chunky wooden bedframe and a standing mirror all handmade from old dhow wood, a ‘cool mist’-blasting fan providing relief from the heat, and hillside views out over the Ruaha river. At night, there are fireside drinks and lively, communal dinners with Noelle and Moli, dishes like garlic prawns a luxury out in the bush.

Kichaka specialises in walking safaris. During two days of walking, wildlife guide Moli points out fascinating plantlife and ‘reads’ the recent prints of buffalo, hippo and lions. We encounter shy kudu and leaping impala, and watch herds of elephants in the forest across the river, later getting up-close to one bull. “The elephant is the greatest creature that ever graced our planet,” Moli whispers, admiringly.

Our third day of walking takes us from Kichaka across the sun-baked grasslands and through woodland towards a wilderness fly camp, 15 kilometres away. The feeling we’re being watched isn’t paranoia; giraffes’ heads poke out above trees, scrutinising us as we cross their terrain.

The day heats up quickly, as we pass candelabra trees and an enormous baobab that could, Moli estimates, be anywhere up to 2,000 years old.

After a moonlit dinner, I sleep comfily in a tent close to the Ruaha, and we continue upriver next morning, led this time by veteran guide Jacques Hoffman. “You really get into things when you’re walking,” Jacques says, as he leads us through tall ‘Suicide Grass’, where buffalo and lion might lurk. “You see the tracks, you see what’s happening. And Ruaha is definitely one if the best places I’ve been. It’s raw Africa, real Africa.”

We make our way towards Kali Forest, Jacques noting fresh lion prints and warning us to be on the alert. There are many more tracks - buffalo, giraffe, elephant… - in the sand, as we work our way up the riverbed, all the time surrounded by the calls of bush shrikes, doves, spurfowl and fish eagles. “Just look around and listen to everything that’s going on here,” Jacques advises us. “It’s wonderful. The amount of life out here in Ruaha is just incredible.”

Wildlife photography courtesy of Graeme Green

Stay:

Jongomero Camp

+255 (0) 22 212 8485)

Kwihala Camp

+44 (0)20 3239 4474

Jabali Ridge and Jabali Private House

+44 (0)20 3239 4474

Kichaka Expeditions

+255 (0) 766 956 627